25 January 2022

Dr David Cutress and Dr Gwen Rees: IBERS, Aberystwyth University.

- Cryptosporidium species pose a significant risk to both human and animal health and welfare

- These protozoan parasites can pass from animal to animal and animal to human depending on the species present

- Several best practice and biosecurity strategies exist to control infection and transmission of both cryptosporidium and other disease vectors at the same time

- Slurry management options should be carefully considered to avoid re-infection, transmission and environmental contamination with cryptosporidium

Overview

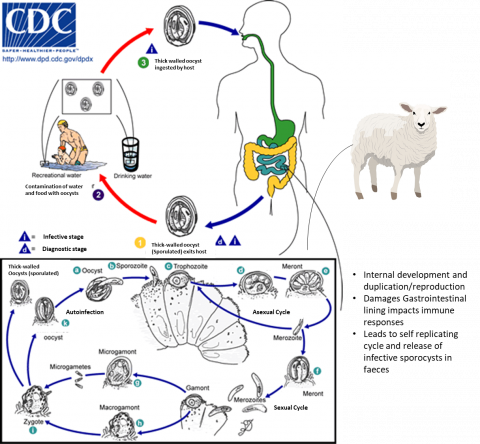

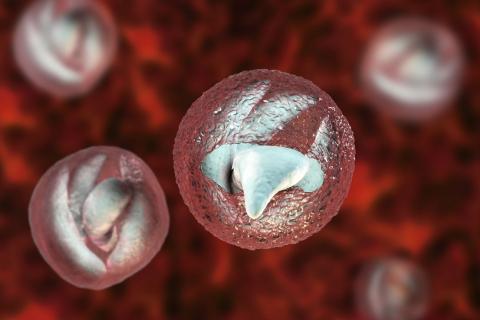

Cryptosporidium species are protozoan parasites which can infect the gastrointestinal tracts of many species, including cattle, pigs, sheep, goats, chickens, horses and deer. Many species of cryptosporidium can also infect humans (zoonotic infection). The main clinical symptom caused by cryptosporidium is diarrhoea, and it is a leading cause of human gastrointestinal infection in the UK. Cryptosporidium is transmitted as oocysts via the faeces of the infected host which can stay dormant for around a year in favourable cool, dark conditions or water due to their tough outer shells. Controlling these tough shelled oocysts can be difficult as they are resistant to several commonly used farm disinfectants and water chlorination treatments. Infection doses can be as low as 10 oocysts in some species. In humans, severity of infection can vary based on age, immune status, and other health issues with the highest incidence in children under the age of 5. People working closely with farmed animals are also at increased risk of contracting the infection, such as farmers, vets and abattoir workers.

Cryptosporidiosis can have significant animal health and economic impacts on all forms of livestock farming. In addition, one of the most significant human outbreaks of cryptosporidiosis in recent history occurred in Ireland in 2007 and had an estimated economic impact in today’s currency of ~£19.5 million (considering inflation). Over the 5 months of this outbreak, 242 cases were confirmed and linked to contaminated water. This necessitated major investment in water treatment facilities. Considering the impact this disease has on human and animal health and the associated costs, it is clear that control and management of cryptosporidium species should be a priority for the agricultural sector.

Image adapted from the Moredun research institute paper (2017)

Livestock impacts

Cryptosporidiosis can cause production and economic losses in farmed animals. Given that, in the UK, the largest value outputs for livestock production can be found in cattle (via milk and meat) followed by poultry, pigs and then sheep, cryptosporidiosis is therefore an important consideration. In livestock, cryptosporidium infections are usually observed in young animals which can show signs of cryptosporidiosis shortly after birth, with key periods of infection demonstrated to be 1 – 3 weeks of age. Several cryptosporidium species exist with different levels of presence in different livestock and human hosts, as well as different areas of impact in the body (Cryptosporidium andersoni impacts the abomasum of cattle for example whilst many other cattle infective species impact the small intestine).

In both cattle and sheep, C. parvum is the main disease-causing species in the UK with previous studies showing UK pre-weaned calf infection prevalence to range from 28 to 80%. In sheep, studies have indicated presence of C. parvum in between 6 – 6.4% of lowland ewes and 9 – 12.9% of unweaned lambs.

In pigs, the prevalence of cryptosporidium species varies massively with estimates ranging from 1-100%. In Sweden improved animal welfare friendly pig production involves changes relating to reduction in the percentage of slatted flooring and loose housing being standard. Studies in these systems have found potential prevalence of 25% with the reduction of slatted flooring and bedding systems used potentially increasing the burden of infection. Compared to other livestock, pigs are noted to suffer fewer production impacts associated with clinical and subclinical infections. This may mean that motivations for disease control in pig production should relate more to general principles of biosecurity (to reduce zoonotic transfer or transfer to other animals in mixed species environments) and environmental protection rather than economic impacts of the sector itself.

Within poultry farming, many species have been indicated to have the potential for infection by cryptosporidium species including ducks, turkeys, chickens, geese, quail, peacocks and pheasants. Different species of cryptosporidium have been noted to infect different poultry species with different results, with some inducing respiratory infections, some intestinal infections and others demonstrating no notable clinical signs. Respiratory infections are noted to be linked to highest mortality levels (up to 90% in young quails for example) with cryptosporidiosis in general noted to have negative impacts on growth performance and grading of meat for sale. With flock prevalence ranging between 22 – 50% across a selection of worldwide studies it is likely that infections have significant economic impacts worldwide.

Transmission and zoonotic risk

Transmission of cryptosporidium species is usually faeco-oral. This can occur either directly (via exposure to faeces) or indirectly by consuming contaminated food or water supplies. Studies in England and Wales have attempted to investigate infections in young lambs associated with reported human infections with C. parvum and found that farm attractions such as petting farms posed a significant human risk. Other studies showed that the risk of infection to the human population was particularly high from young calves, but risk of transmission was also important from rodents, birds, farm waste and soil. A single calf has been demonstrated to be able to shed over 100 million oocysts during infection. Given that as few as 10 oocysts can lead to infection, this means one infected calf has the potential to infect up to 10 million people or animals.

Recently, genotype analysis has allowed the tracing of specific infections in Wales and England from 2009 - 2017 from various sources and subtypes and has found that 46% of human outbreaks of cryptosporidium infection occurred due to recreational waters not associated with livestock, whilst 42% occurred due to animal contact. Only 4% and 1% of infections were associated with environmental contact and water supply contamination respectively, suggesting that water protection and monitoring regulations introduced in 1999 have been effective at mitigating risks from contaminated waters. Despite this, it is still clear that livestock pose a significant risk to human infection and thus the continuation of cryptosporidium infection cycles on the whole.

While environmental contamination is of lower risk for human transmission, it is still a risk for animal-animal transmission. Livestock release oocysts in their faeces which are then incorporated into manures and slurries and are spread on agricultural land as fertilisers. This process can cause high infection risks associated with soils and pastures (for grazing animals and wildlife) and through combination with poor slurry timing and wet weather can lead to surface run off and downstream water system contamination.

Despite livestock being significant sources of Cryptosporidium species environmental contamination, many other wildlife species may well play key roles. Studies have indicated wild deer populations and geese populations in areas where previous cryptosporidium water infection was diagnosed suggesting alternative or intermediate impacts involving wildlife. Insects can also carry cryptosporidium externally and internally which may also impact transmission between species.

Diagnosis

A key aspect to both understanding and controlling infection risk is being able to accurately diagnose the infection in the first place. It is essential that this diagnosis is performed with the assistance of professional veterinary experts. Whilst observation of clinical symptoms can be also be used these are often not specific to cryptosporidium alone and as such definitive diagnostics should be performed. Generally, diagnosis can be performed via microscopy of animal faeces and specific staining, however, this requires samples to be sent to a laboratory. On-farm point-of-care lateral flow-based tests are less sensitive but far quicker and can be beneficial to be utilised regularly to keep on top of infection risks across farms. For determining specific species of cryptosporidium present, various PCR techniques are available following DNA extraction but again this requires laboratory testing.

Transmission pathways of Cryptosporidium taken from Innes et al., (2020)

General control and treatment strategies

Generally, employing biosecurity and hygiene improvements and best practices will also reduce cryptosporidiosis risk in livestock. Veterinary produced herd and flock health plans are one of the most important tools in controlling cryptosporidiosis as well as many other diseases and improving wellbeing overall. Young livestock animals are considered one of the key sources of infection due to their significantly high oocyst shedding in faeces. As such, prevention of infection at birth and during the following period is vital. The life cycle of the parasite allows it to multiply rapidly because infected calves shed millions of parasites into the environment. This can lead to very high levels of oocysts in the environment which is a source of infection for young animals in that environment. Because the parasite survives well in the environment and is not killed by most standard disinfectants, steam cleaning is the most effective method of disinfection. Mixing of calves can perpetuate disease, with younger calves becoming infected therefore it is advisable to regularly steam clean housing and to avoid mixed age groups where possible. Hygiene within farm buildings, particularly birthing pens, is vital along with separation of animals away from potential contamination sources. These simple considerations can go a long way towards reducing cryptosporidium impacts on farms. Hygiene surrounding feed and water sources is also vital, to remove these as a potential infection risk and long-term contamination reservoir for the tough shelled oocysts. Currently, licensed treatments for cryptosporidium consists of halfuginone for cattle which reduces symptoms and oocyst shedding, but is only effective if utilised quickly following onset of symptoms and generally only advised in high herd incidence levels. When considering disinfectants, many commonly used products are ineffective and research has highlighted that those containing hydrogen peroxide have the biggest impact on killing oocysts whilst other research has shown benefits surrounding hydrated lime pen disinfection. Furthermore, steam cleaning can produce the temperatures required to inactivate oocysts so should be considered particularly during lambing/calving periods. When animals are known or suspected to have an infection it is vital they are separated for longer than it takes for symptoms to stop (usually up to 2 weeks following symptoms) as during this asymptomatic period they are likely still shedding oocysts. Due to increased impact on animals with compromised immune systems, a key aspect of cryptosporidium management is in ensuring adequate immune protection and nutrition via early colostrum management. Some studies have even demonstrated that mothers immunised with cryptosporidium proteins can generate hyperimmune colostrum which could act as a viable management strategy in the future. Of note, a European Innovation Partnership (EIP) project is seeking to further highlight risk factors associated with cryptosporidium and biosecurity, water contamination, general hygiene and nutritive impacts on infection levels and risks in sheep and lambs to farmers across Wales.

Novel treatment and control strategies

As well as ensuring slurry is not spread during wet periods, to avoid any potential run off and contamination of environments via slurry containing cryptosporidium oocysts, studies have assessed ways to reduce oocyst survival within the slurry itself. Correct composting to achieve heats greater than 60°C and low pH values both help inactivate oocysts making anaerobic digestion a promising option. One study found that the addition of low levels of ammonia to slurry could reduce detrimental bacteria survival and cryptosporidium viability, though this may have negative connotations towards environmental impacts long term. Whilst other early studies have indicated by-products from the brewing industry may have anti-cryptosporidial activities which could be incorporated into slurries or directly into risk animal feeds. Interestingly riparian buffer strips have also been noted to play potential roles in slowing or preventing transfer of oocysts (and other pathogens) into water-sources alongside their multitude of other environmentally beneficial effects.

Economic impacts

Multiple studies note the potential for high economic burdens associated with disease, veterinary intervention and loss of productivity associated with cryptosporidiosis in livestock. Despite this, accurate and in-depth research into the cost implications of this disease in cattle are not readily found though some upcoming data from the Moredun Research institute may shed more light on this in due course. Previous research indicates that whilst mortality is not the major economic burden of Cryptosporidium species where cattle are concerned it has been observed that mortality rates related to calf neonatal diarrhoea syndrome (heavily associated with infection by Cryptosporidium species) were between 5 – 10%. Utilising prevalence and mortality figures it could be suggested that mortality impact alone via cryptosporidium infection could reduce prime cattle numbers by between 28,500 - 163,000 a year. These losses in meat based on current steer prices and average carcass weights achieved in the UK would equate to economic losses of between 2 – 9% of the UK’s total £2.8 billion annual beef supply chain.

Given UK lamb figures for 2020 and utilising between 30-50% mortality rates suggested for cryptosporidium in goats and calves (as mortality levels in sheep are understudied), this equates to the possible death of between 207,900 – 496,650 lambs a year with an economic value of ~£40 - £100 million pounds if all lambs reached weights of 41.5kg at current UK sale prices. Even if mortality rates are not this high for sheep (which is debatable as previous research noted that mortality and morbidity tend to be higher in lambs than calves) it is well documented that infection with cryptosporidium can have associated management costs in lamb rearing and long-term impacts on lamb weight gain and productivity which will all factor into economic burdens.

Summary

Cryptosporidium infections pose a high risk to animal and human health and are likely having significant economic impacts on multiple livestock sectors. In order to reduce any potential livestock suffering and increase economic potentials on farms, multiple control considerations should be considered:

- Good hygiene and management, particularly around birth and young animals

- Improved biosecurity – Including secure fencing to avoid external wildlife infection risk and water-source infection risks

- Good indoor hygiene – including water and food sources, consideration of disinfectants used and steam cleaning

- Good colostrum management

- Implementation of quarantine procedures and having facilities to perform these

- Optimal slurry spreading – utilise weather predictions and advised spreading period guides

Where farms are open to members of the public, and in particular to children it is essential that the above considerations are employed, and that increased biosecurity is considered surrounding hand washing and potentially avoidance of human interaction with young animals specifically.

If you would like a PDF version of the article, please contact heledd.george@menterabusnes.co.uk