6 April 2022

Dr David Cutress: IBERS, Aberystwyth University & Kate Hovers (MRCVS)

- The goat industry appears to be growing both in the UK and globally

- Optimising production and welfare relating to differing goat biology compared to other ruminants requires more investigation regarding parasites and drug dosages

- Goats offer some unique potentials as a livestock animal of increased use but veterinary advice and research on good practices and treatment need to move away from assumptions that sheep act as a comparable model

- It is essential to seek veterinary advice before embarking on any treatment of goats to ensure appropriate and effective strategies are utilised

Goat farming in the UK

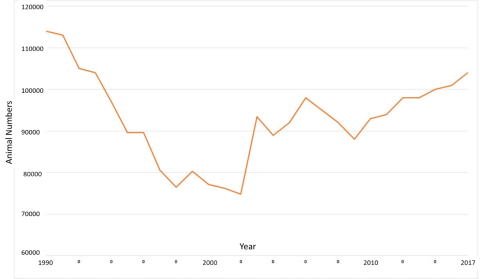

Goat farming in the UK saw a series of huge increases, including an approximate 20% year on year expansion between the late ’90s and early ’00s, with a slower steadier increase from 2010 onwards. Whilst at least half of these numbers appear to be related to the British dairy goat industry these systems still produce meat from breeding their lowest-performing milk animals to meat breeds (similar to the dairy cattle industry). Globally individual’s consumption of goat meat per capita per year increased almost two-fold between the 1960s and 2010s and goat numbers have seen the largest increase of any livestock animal in the last decade, suggesting that this is a growing market. Much of the growth may be related to the positive nutritional benefits associated with goat meat due to its low fat and cholesterol contents for red meat, particularly as many consumers move towards more health-centric purchasing choices.

Goat numbers in the UK from 1990 to 2016

Despite the increases in goat numbers, published research relevant to UK goat farming is scarce and largely focused on milk production with some goat research coming from European temperate regions but far more being related to tropical and sub-tropical regions where numbers are higher. As such there are likely UK centric challenges to goat farming which could be hindering the sector's growth. A UK wide survey utilising the members of the ‘Milking Goat Association’ in 2019 reported key issues surrounding pneumonia, scours, failure to conceive, need for assisted kidding, Johne’s disease, tuberculosis and correct nutrition in UK goat farming. Furthermore, the same survey identified a significant lack of outdoor grazing of goats (only 17% of UK dairy goat farmers surveyed grazed goats outdoors) this was partly due to the known susceptibility to infections from gastrointestinal nematode (GIN) parasites. Whilst parasites are a relatively lower issue in milking goats due to tendencies for indoor systems being easier to manage with larger numbers of animals, welfare and wellbeing initiatives across all livestock production may well push producers towards supplying at least partial outdoor access, which could make parasite infection a significantly larger issue.

One of goat meat production’s most desirable aspects is the significant adaptations for animals surviving and thriving in marginal areas where land is unsuitable for most agricultural applications. Goats as such have a higher tendency to browse shrubs and other marginal vegetation as opposed to grazing like sheep and should naturally come into contact with fewer parasite transmission opportunities. Due to this many goat species have under-developed immune responses to initial exposure to parasites making them less resistant to infection whilst also failing to mount significant responses to continued challenges.

Parasite infections in goats

Modern husbandry for goat farming has shifted goat feeding away from marginal browsing in many instances towards pasture-based grazing (for ease of management and determination of energy intake from forage amongst other reasons). When combined with mixed-species grazing or rotational grazing with multiple species, this places goats at a higher risk of interaction with infective parasite stages. Goats have been confirmed to be susceptible to many of the same diseases as sheep and cattle inclusive of parasites where goats are susceptible to the same pathogenic species as sheep with some variation surrounding Teladosargia, Trichostrongylus, Haemonchus and Fasciola species. Infections in goats can lead to symptoms including reduced appetite, diarrhoea and weight loss and lethargy alongside specific symptoms dependent on parasite locality within the host (such as bronchopneumonia and emphysema when located in the lungs). All of these alone or combined can impact the productivity of animals leading to reductions in meat, milk and reproductive successes. In acute cases, infections also increase mortality rates as such parasites pose a clear threat to animal welfare and wellbeing.

Immune implications and drug metabolism

Several studies have demonstrated that immune responses to GIN species in goats are far less effective than those seen in sheep, full expression of immune responses can take almost twice as long in comparison (12 months – goats, 6 months – sheep). When immune responses do develop in goats they tend to relate to reducing internal larval growth and affecting egg production, as such they are still highly susceptible to the initial establishment of larvae and the damage associated. This suggests further benefits to control mechanisms that would reduce or prevent interaction with initial infection routes on pastures. Further, challenges include the difference in immune memory suggested between goats and sheep where goats immune responses appears to be far shorter lasting as indicated by similar infection levels in young and adult goats compared to sheep where resistance developments lead to lower burdens in older animals. Put simply, without low-level chronic infections, or regular reinfection, goats’ immune systems appear to ‘forget’ how to respond, however, this does not suggest purposefully exposing goats to wormy pastures is advised. Combined with these immunology considerations, goats have been noted to undergo different pharmacokinetics (drug impacts on the animal) to sheep, despite this, there are currently only a handful of eprinomectin products with published licensed dosage rates specifically aimed at goats in the UK. Goats metabolise compounds faster than sheep so dosing at the same rates can lead to underdosing and survival of a population of parasites that have interacted with compounds and are more likely to develop resistance. Furthermore, it is known that there can be issues surrounding applications of drug dosages based on the correct animal weight in sheep farming and similar actions in goats could have even greater impacts on dosage efficiency. Furthermore, the limited availability of licensed treatment options for goats could play roles in unauthorised treatment. Licensed dosage and usage advice of prescribed drugs in other livestock animals prevent chemicals from entering the food supply chain by remaining present in meat and milk. Unauthorised treatments in goats may have variable withdrawal periods (particularly due to their differing metabolisms) leading to animals or animal products entering supply systems and posing a risk. As such farmers are advised against such treatment options. In response to some of these knowledge gaps, a ‘European Innovation Partnership’ (EIP) project has been ongoing through Farming Connect across four goat meat businesses in Wales to start looking at dosage impacts in goats as well as other parasite impacts specific to the UK.

Control

Control strategies from a previous GIN article with regards to sheep and cattle can also be utilised in goats, this is inclusive of seeking veterinary advice towards producing overarching well-considered health plans on farms. As is continually noted across livestock sectors biosecurity is a key consideration where disease vectors are concerned, due to the growing nature of the goat sector, careful inspection and quarantining of any bought-in animals is vital. Other control options include targeted selective treatment (TST) and maintenance of refugia pool of parasites which may offer particular importance in goats due to the need for sustained infection presence to maintain any immune responses (and also due to a higher risk of resistances occurring). As with cattle, there is some speculation surrounding goats with regards to using medicinal plant compounds with effective anthelmintic properties. Goats offer even further potential due to their browsing adaptations allowing them to have higher toxicity thresholds for many medicinal compounds. This in some instances may offer the potential to dose heavily enough to impact parasites without impacting goats negatively, though notable exceptions exist including issues surrounding higher Levamisole toxicities found in goats over sheep. Previous immune markers were suggested to be implicated with worm burden in specific goats via eosinophil and IgA counts. Whilst more recent studies have failed to find significant evidence of these as markers for parasite resilience in goats, there has been substantial research that indicates resilience and lower worm burdens are heritable traits that can be bred for down lineages. Regular faecal examination via faecal egg counts (FECs) and flotation methods to help determine parasite species present (via McMasters FLOTAC combinations or automation integrated FECPAK systems) should be a routine component of control. Knowing parasites present and severities can assist in making management changes and informed treatments. Where goats are concerned, however, it has previously been noted that levels of eggs per gram (EPG) associated with negative animal health and productivity impacts can be variable between breeds. This may outline an area that requires further research and refinement to ensure correct treatment timing when utilising anthelmintics and TST for example.

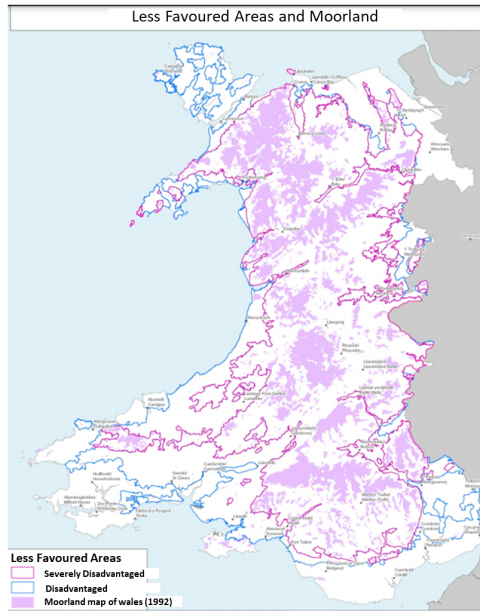

Previous studies comparing grazing and browsing options on sheep and goats and the impacts on parasite infection demonstrate that if forced to graze, goats are far more susceptible to infection than sheep, however, when browsing, goats fared far better with less intense adult goat infections. This would indicate that utilising goats in marginal lands and less-favoured areas (LFAs), as well as a key benefit due to their high adaptability to such areas (turning low-quality land into high-quality meat), would concurrently work as a strong parasite control option. At the same time, goats could have a positive impact on LFA and upland areas (which are proportionally high in Wales, see map below) towards species diversity and maintaining vegetation and land equilibriums with roles including control of reforestation which can impact fire protection in some areas.

From 2014s review into the resilience of Welsh farming

Summary

Goat farming should be viewed as an adaptable alternative to other ruminant grazing, dairy and meat systems in the UK. Whilst goats have their own challenges with regards to management and production, limited UK specific research has been performed on these systems. Instead, we are hugely reliant on modelling goat production on sheep systems or utilising tropical regional studies. This is a significant knowledge gap that needs to be rectified by targeted experimentation and trials, as it is known that goats have very different immune and drug metabolism responses. Parasites and their accompanying resistances are a key area of concern across ruminants for welfare and production burdens. In goats, these pose an even greater concern due to lower resistances and resilience observed in many goat breeds compared to most cattle and sheep. If these concerns aren’t addressed they may hinder the sector’s growth potential, which otherwise could have high value, particularly in Wales, due to goats strong performances on marginal lands and potential for positive associated environmental impacts.

If you would like a PDF version of the article, please contact heledd.george@menterabusnes.co.uk