16 August 2021

Dr David Cutress: IBERS, Aberystwyth University.

- Indoor environments and infrastructure can have a significant impact on livestock welfare with many regulations and best practice guides affecting this

- Often a perceived core concern of indoor welfare is space allowance, whilst this can be essential many other factors can be equally as important

- It is impossible to provide general parameters such as stocking densities that are optimal across all farms, farmers should work with experts to perform accurate welfare assessments to optimise infrastructure on a case by case basis

Livestock welfare and wellbeing

In the UK the welfare and wellbeing of livestock animals are governed by a set of rules known as the ‘Welfare of Farmed Animals’ regulations. These specify minimum requirements surrounding space, bedding, lighting, ventilation, hygiene, feed access, water access and indoor environments. These aspects of farm infrastructure are vital as it is well known through farmer experience, as well as research, that the environments of livestock animals can have a significant impact on their wellbeing with knock-on impacts on productivity and sustainability. Factors such as temperature can impact animals via heat stress, cold stress or by providing beneficial environments for disease vectors to thrive and for infections to spread. Ventilation can impact cooling, humidity and gas build-up but also plays roles in reducing the spread of infectious airborne diseases and reducing dust particles which can affect animal and human respiratory health. Bedding comfort, cleanliness and moisture retention can impact animal lying bouts and durations. Bedding also has impacts on disease vector growth and survival and occurrences of livestock diseases such as lameness. Feed and water placements can be key within indoor systems as these become areas of high traffic impacting nutrition, hydration and hygiene as well as social behaviours for dominance within-herd structures. Floor-type has considerations for compromise between animal welfare (comfort for animals and cleanliness) against durability and longevity desired by farmers. General space for movement such as passage width and housing area space are all suggested to impact animal stress and behaviour particularly surrounding feeding and dry matter intake (DMI). Highly stocked indoor environments also relate to reduced health and increased disease risks, with suggestions that stocking density has higher importance than ventilation when it comes to respiratory diseases for example. Whilst lighting cycle changes have been demonstrated to affect an animal’s levels of circulating hormones which impacts immune responses. There are many considerations when designing or retrofitting a space to house animals short or long term. However, it is also worth noting that each element that can impact welfare and wellbeing is itself subject to many different factors (animal age, breed, local environment and social hierarchy for example).

Building plans and considerations

In humans, there can be a difference in effective building designs which provide “survival needs” rather than those which offer “wellbeing” needs, both of which can function towards affecting overall health. Similarly, in livestock bare minimal survival needs can ensure a basic level of health but going beyond and focusing on wellbeing can have significant benefits. Furthermore, infrastructure design has significant roles across the board in agriculture with regards to climate change (building insulation, ventilation, renewable energy sources, energy efficiencies, waste management) farmworker health and safety and economics. Developing buildings and environments for improved wellbeing can also lead to increased production and often improved quality. Welfare assessments are key tools that farmers should be aware of in designing any infrastructure to be fit for purpose. These evaluation tools look at four major principles as can be seen when considering poultry below.

Adapted from Assessment protocol for poultry Welfare Quality with welfare criteria 8 omitted

Space

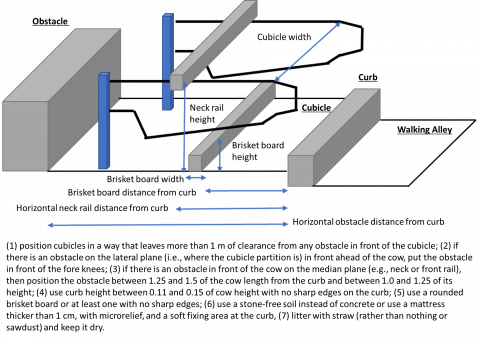

A recent analysis of 76 dairy farms using welfare quality assessment tools suggested refinements to cubicle designs for dairy cows relative to individual cow sizes (see below cubicle diagram) towards improving welfare associated with skin issues, lameness and general hygiene.

In both traditional parlour and automatic milking systems (AMS) linked to indoor freestall housing, stocking density has been assessed. Commonly overstocking was found to reduce space available for lying thus reducing ruminating, increasing aggression and reducing individual performance whilst increasing disease and health risks. Thus, farmers should strive for 100% of animals to have access to feed and lying spaces at any one time within a system. Other indications for dairy cows implicate optimal neck rail height in improving hygiene and thus reducing disease occurrence. Furthermore, whilst providing access to pasture in cattle is the ideal design, where this cannot be facilitated it is important to provide access to other outdoor spaces as these can be positive for cattle behaviour. In pigs, the space provided for farrowing and rearing have demonstrated different effects. Studies suggest higher welfare from piglets farrowed via group-housing of sows with litters compared to use of farrowing crates and single-housing free farrowing pens. However, following farrowing, conventional rearing systems (which provided almost half the space of wean-to-finish pens) showed little to no benefits suggesting space considerations vary within livestock rearing life cycles. Similarly, in ewes, lower space allowance has been associated with lower milk yields, lower feed intake and thus lower productivity. Whilst decreases in aggressive behaviour and thus increases in lying times have been found with 1.5 m2 space allowances in pregnant ewes, little benefits were observed in space increases higher than this. Designing areas where indoor housed sheep can have free access to outdoor pens have shown multiple health and welfare benefits. Whilst space has been heavily discussed within the poultry industry, agreements surrounding impacts have been difficult to achieve. Individual animal factors can affect space needed with a recent comprehensive review suggesting that the focus should not be on minimum space per animals as designated by codes of practice or space per weight of the animal, but instead be focused on the space needs for the animal to perform each behaviour or activity.

Bedding

Straw bedding in dairy cows was dirtier in lower space allowance systems and milk lactose levels were higher indicating an increased potential of mastitis. Where straw is used as bedding larger areas per cow and routine cleaning of straw and infrastructure to keep it dry are vital considerations. A recent analysis of welfare indicators in loose housing systems in cattle have suggested that correct management and best practices are far more important to improving welfare compared to the specific bedding utilised. Furthermore, freedom of choice experiments suggested that cattle chose increased space over preferential bedding. As such a farmer’s core concern should be space provided rather than lying surface material. This suggests farmers should focus on the economics and sustainability of bedding choice whilst optimising their current systems by utilising welfare quality assessments to highlight weak points. Bedding, compared to no bedding, in multiple species including pigs and lambs has been associated with improving positive behaviours and can synergise with other factors such as increased space per animal. Whilst bedding comparisons have been performed for sheep little productivity or quality differences appear to occur if managed correctly, though a study showed evidence that straw and cellulose beddings (a paper industry by-product) reduced stress responses over sawdust and rice husk. When considering poultry (and landfowl in general), a recent meta-review found that the favoured beddings were sand and peat moss which provided an enriched environment. Furthermore, bedding depth and absorbance qualities between materials in the poultry sector have been indicated to have roles in controlling moisture and footpad dermatitis levels. As such significant depth of bedding should be maintained (>7.6cm in a peat moss vs wood shavings study) as well as considering bedding type to balance moisture impacts on animal health alongside economic and environmental impacts.

Lighting

In cattle different lighting cycles, used at different times in the reproductive cycle, can increase overall milk yields and days in milk, but also these cycles can have some positive health and welfare impacts. In cows in the lead up to calving, as well as calves, short day photoperiods (6 – 8 hours of 120-200 lux) could enhance immune functionality and even reduce the length of dry periods (where increased mastitis can occur) thus benefiting health. Farmers should consider blackout blinds along with commercially available controlled lighting systems to control photoperiods of indoor cattle and shifting outdoor grazing times throughout the year dependent on light levels as well as pasture availability. Generally, cattle are known to prefer to move from low to high light areas. As such infrastructure should have sufficient lighting to ensure all areas are well lit as cattle may avoid dark corners, effectively reducing your available space. Furthermore, farmers may want to consider the colour of lighting as yellow light rather than white and blue has been suggested to improve feed intake, rumination time, water intake and body weight gain particularly in calves. In broilers, studies show significantly high-intensity lighting as being associated with eye damage and changes to feeding, productivity and aggressive behaviours. Generally, lower lux lighting should be considered as broilers preferred pens with feeders or waterers at 20 lux compared to 5 lux subsequently leading to increased feed consumption. This suggests providing higher lighting in areas around feeders could encourage feed uptake whilst providing lower lighting in other areas would allow natural resting behaviours and reduce aggressive interactions for overall improved welfare. In sheep, photoperiod is known to play roles in feed consumption (with low light <10 lux reducing intake) and reproduction. In sheep, light and welfare is relatively understudied, likely due to sheep being utilised mostly in year-round outdoor systems where controlling light is impossible. Though papers have indicated light levels of between 10 – 500 lux as the range within which the optimum for sheep exists and that green light can improve feeding and reduce resting times in lambs.

Ventilation and temperature

Temperature, humidity and floor type have all been seen to interact in pig studies which found that animals were more likely to excrete on and foul solid floors as temperatures increased and even at lower temperatures where humidity increased. Pigs also change their lying behaviour on slatted floors as these areas can be around 3 - 4 °C cooler than solid floor regions. Space and temperatures were demonstrated to have key effects on lamb development where overnight environments (domes/insulated overnight sheds) provided higher temperature environments allowing higher body weight gains and milk intake which could reduce overall lamb mortalities. Whilst ventilation and air space minimums per sheep in studies have been well assessed for improving health and reducing microbial risks, in a recent ‘European Food Safety Authority’ study in Italy, milk, wool and meat production of sheep across a range of systems showed that heat stress was consistently a core concern. This suggests farmers should carefully monitor and optimise their indoor environments towards optimal sheep temperatures as a priority over other welfare factors. In cattle systems, fans and “sprinkler” systems can all benefit the cooling of animals with conductive cooling being the newer more economic and sustainable option. Heat is currently less of an issue in the UK, however, research indicates that as many as 20 days a year where temperatures are sufficient to cause mild heat stress, could become the norm in future making this a growing consideration. A larger UK concern is the impacts of poor ventilation on favourable pathogen conditions, compromising animal immunity, leading to build-ups of noxious gases and causing draughts which impact housing temperatures. Most ventilation systems require capital investment and add running costs. As such it can be vital for farmers to consider their general structures, airflow and insulation carefully before investing further. Some simple mechanical ventilation of inlet and outlet flows following assessment with smoke clearance techniques can be easily achieved. In poultry systems, a large concern for GHG impact and welfare is the heating of poultry houses. In poultry and all other livestock systems where heating is required, there must be a balance between animal welfare and sector energy efficiency, as such it is advised that farmers consider alternative energy and heat generation methods (see previous article) as well as bedding and building insulation qualities and improve these where necessary.

Hygiene

Studies in dairy cattle link hygiene with beneficial behaviours of lying, where cows lay longer in cleaner comfortable environments and had lower occurrences of lameness where good cleanliness and bedding hygiene was maintained. Regular leg hygiene and cow hygiene scoring performed by farmers can be a key tool to reduce lameness and also improve udder health. Calving is a key health risk time so having infrastructure of multiple calving areas to allow cleaning between calves, thus reducing infection risk, can be beneficial. In sheep rearing lambing is a risk period with high numbers of mortalities and illness causing production losses and welfare concerns across the industry. Hygiene surrounding mothering pens is a factor as well as hygiene of colostrum-feeding equipment if artificial or pooled cow colostrum is used. This is equally a concern in cattle as a sampling of 56 UK dairy farms found that colostrum collection buckets and feeding equipment were bacterial risk points and noted the need for farmers to follow stricter cleaning within colostrum collection protocols. Of vital consideration in infrastructure design with regards to hygiene and biosecurity is ensuring dedicated livestock structures to provide quarantine zones for any potentially infectious animals or newly purchased off-farm animals, or sufficient space within your main structure to isolate animals.

Feed and Water access

Providing optimal cattle feed bunk space can reduce negative feeding behaviours and improve feed intake and rumination activity as low levels of space are known to be detrimental, particularly for cattle lower in the social ranking. Competition at feeding can be influenced by the feed barriers utilised as those which help to separate adjacent cows may reduce negative behaviours. Where applicable providing headlock barriers to animals during feeding offers a sense of protection but it is important to consider sizing them suitably for bunk space dependent on breed used and take in factors on feed rail height such as those noted earlier in the article. Cattle are noted to prefer to drink from larger troughs with hygiene being a key factor where these are fouled by manure and become an infection risk. Farmers should consider regular cleaning schedules and sufficient trough access and space to avoid competition and avoid fouling. In goats, the evaluation of the height of feed supplied in bunks (floor vs head level) indicated that whilst increased feed heights improved intake it may have negative behavioural implications by increasing feed displacement events. Feed and water considerations seem understudied in sheep as a comprehensive review of sheep housing welfare failed to mention feed or water considerations entirely. Though one study has suggested farmers should utilise blue and yellow coloured waterers over black varieties and clean these regularly (every 1 – 4 days) to improve water uptake in sheep. In pigs, feed situations have implications on welfare in a variety of ways. Studies have found that where feeders allowed separation from main living areas animals spent longer in feeding stations particularly if their main area had higher stocking densities. However, this makes these an area for competition of access which could lead to aggression (vulva biting etc). Providing individual housing and feeding can alleviate this and improve feed intake. In poultry some have noted that water in commercial houses supplied via nipple drinkers is a highly unnatural situation, however, open sources of water can add humidity and dampness to litter as well as being an infection risk. Controlling wet litter in poultry barns is a key consideration with increased water intake being noted in stressed birds, as such farmers should attempt to reduce stress as much as possible in all other areas to control water intake and optimise growing conditions.

Building and materials

Across all agricultural infrastructure, materials must be used that can be easily cleaned and disinfected to improve hygiene and reduce disease risks. Multiple studies in cattle have demonstrated that slatted floors with rubber matting compared to concrete floors improves comfort, locomotion and leg and claw health. Whilst provision of enrichment objects such as brushes, plastic chains and rubber teats seem to reduce negative behaviours in calves and cattle and can increase rumination time when animals are required to be housed alone. Rubber matting has also shown comfort and reproductive welfare benefits in sow breeding. Providing enrichment items may reduce negative social behaviours in sows particularly in large stocking densities which lacked bedding enrichment. Goats in intensive indoor systems show a preference towards solid rather than slatted floors with straw and rubber areas being favoured for lying. Recent analysis in poultry has looked at perforated or partially perforated flooring as a rearing surface over traditional beddings such as wood shavings with indications that these could benefit production rates, reduce injury risk and potentially benefit air quality by reducing carbon dioxide and ammonia. Similarly, slatted flooring also demonstrated air quality, microbial contamination and immunity benefits in broilers compared to traditional deep litter systems. This along with litter wetness issues described above suggests that poultry systems should look to move away from litter-based flooring systems for both animal health and environmental reasons.

Finally, innovations on traditional building materials have the potential to not only reduce agriculture building design costs but also be combined with added benefits. Examples include using diatomite lightweight concrete blocks which reduces costs whilst improving heat retention compared to traditional equivalents. This can reduce heating needs and provide comfortable temperatures for housed livestock. Unglazed transpired collectors (UTCs), which essentially turn sun rays into warm air, could increase indoor system temperatures using minimal energy inputs from fans to circulate the energy captured. For more information on energy-efficient and environmentally considerate agricultural infrastructure aspects such as solar reflectance and use of heat exchange see this previous article.

Summary

Animal welfare is a vital aspect of livestock production. Multiple studies and reviews have been performed over the years often comparing particular species’ housing systems to each other directly. With increasing knowledge and information about best practices becoming available it is important that producers worldwide are informed of these so that they can adapt and improve management systems. In a 2016 study of 27,000+ European citizens from 28 countries 94% of respondents considered animal welfare protection of farm animals to be either “somewhat important” or “very important”. This suggests consumers appreciate high welfare and may even suggest welfare associated food labelling could warrant higher associated sale prices, similar to organic. Such strategies and tools could improve welfare on farms and help facilitate a strategy of “less but better” which could be one sustainable option for the future of farming.

If you would like a PDF version of the article, please contact heledd.george@menterabusnes.co.uk